Featured on the Arts page of the Otago Daily Times, Thursday, October 12, 2017

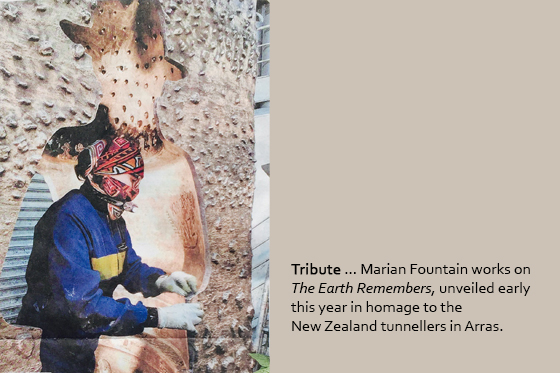

Paris based New Zealand artist, Marian Fountain’s works are being exhibited at Fe29 Gallery in St Clair this month. As she explains to Rebecca Fox, one of her greatest honours has been to create a bronze monument as a tribute to New Zealand tunnellers in World War I, in Arras France.

Q Is there any particular work or series of work that is a favourite or stands out for you?

‘The Earth Remembers’ monument stands out for me because it was made for the people of NZ and France about our common history, and it will live it’s own life from now on.

Q – What did it mean to you to be commissioned to make a statue to mark the First World War centenary commemorations at the Carrière Wellington Museum, Arras, France?

It was a huge honour and responsibility. Finding the idea took time but once it was there it was complete and nothing needed changing. Immersing myself in the subject of WWI was very subduing, I took my role – of representing the people who suffered and the need to condemn war – very seriously. It was a 4 year process and the fabrication itself took 22 months.

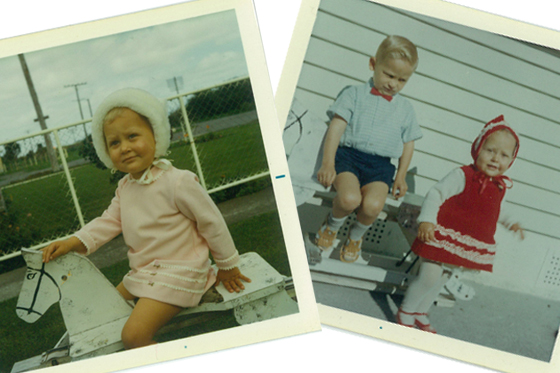

Q – Where did you grow up?

In Papatoetoe, South Auckland. We lived off the garden which had 36 varieties of fruit, there were vegetables, chickens, and the occasional lamb. When I was 7yrs the family moved to Whanganui where I stayed till returning to Auckland to go to art school.

Q – Did you always know you wanted to be an artist? How did that evolve?

As a young child I was often wrapped up in observing a leaf or stick, creating scenarios with objects. The sense of wonder has always been there, I felt that a scientific career would inevitably become too specialised, and that by making art I could discover more about the universe and our existence by playing with juxtaposing ideas.

Q – How did you come upon sculpture and medal making?

Professor Beadle at Elam School of Fine Art introduced me to his techniques in his fascinating world of working with wax. As he became too ill to work he passed on some commissions to me : portrait plaques of the former deans of the art school, and a sundial for Auckland Medical School. So the first year after art school was a formative time for learning how to create art work in the real world.

Q – What is it about these arts that have grabbed you and hold you?

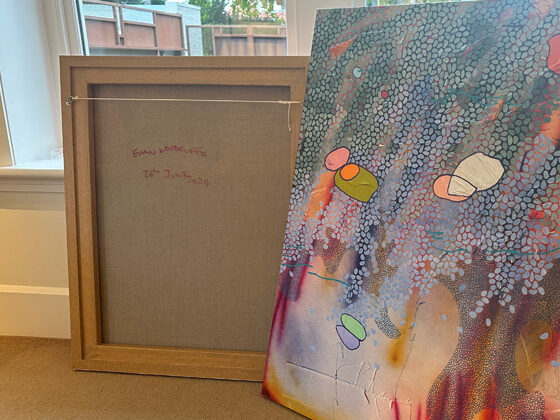

Bronze is a material which has a rich history in many cultures through time. Making sculptures with this age-old process seems to bridge time, informing us at once of our present and our distant ancestral past.

In the process of making a sculpture I mainly work with plasticine, wax and plaster. They are natural materials which are pleasing to manipulate, not toxic. The negative and positive steps in mold making add more stages in which to intervene, building up a situation of many creative possibilities.

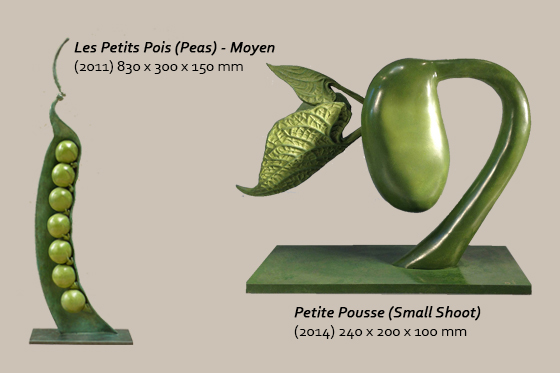

I work alternately between small and large scale: a large work is concerned with form and presence, whereas a hand-held object lends itself to a more narrative intimacy, whereby one can hone in to the microcosm as though looking through a microscope, to find out about the nature of something.

Q – How has your work developed over the years?

Arriving in Europe in 1984, the multitude of cultures, styles and eras led me to look for a certain essence or universality. A period of museum research ensued, culminating in an exhibition at the Museo Archeologico di Milano, where I exhibited in the Etruscan room, proposing a series of objects from a ‘yet undiscovered’ or ‘possible’ culture.

In contact with contemporary artists in Eastern Europe during the early 90’s, my work underwent a transformation, and ‘metamorphic’ tendencies evolved in direct response to shifting politics and the changing situation for Eastern-bloc artists. With the series of ‘beings in transition’ I was analysing the actual structure of change. At this moment I got ‘out of the museums and into the subconscious’.

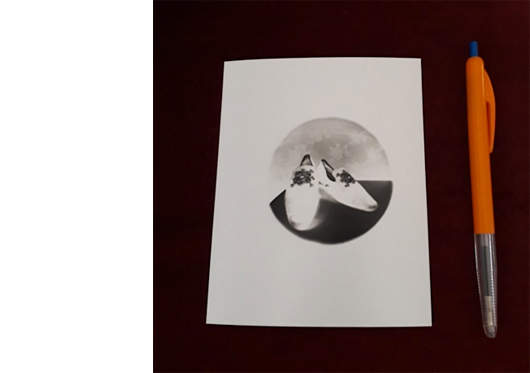

The Remote Control series (2000 – 2010) looks at our evolving relationship to touch and form in our everyday lives, with levers and buttons replaced by touch screens.

Q – What is it like making medals for things like commonwealth games etc?

First I try to imagine the spirit of the finished object, then brainstorm the possible aspects of the subject by drawing a lot of possible scenarios. It’s then often a process of elimination to hone down the design to a satisfying whole.

Q – How is technology impacting on casting in bronze if at all?

I’m starting to use 3D printing for making some effects at the model stage. The actual casting process is age-old, but foundries in the Paris region are becoming scarce.

Q – Why move to Europe and settle in Paris?

I was attributed a QEII Arts Council Grant in 1984 to study foundry techniques in Europe, first training at the Italian Mint School in Rome before living for a time in London. In my travels Paris became a mid-way point that became more and more essential, I made friends here and took up the opportunity for free studio space.

Q – What do you like about living in Paris?

Everyday conversations here have always been inspiring. I’ve lived in 3 different neighbourhoods each with their own particular feel and history, and there will always be more to discover. The diversity and resilience of Parisians inspires confidence.

Q – What is a ”normal” day like for you?

Every day is different, starting with meditation I then get on with the most urgent thing whether it be the project or sculpture at hand, meeting people or administration, with exhibition visits and communal gardening whenever possible.

Q – How does your NZ background influence your work?

Nature and the land is our life-source. It’s enriching to have grown up in contact with the Maori culture : the presence of another world view from that of Europe, with different creation stories, customs, understanding of nature and the land, language …and reasons for making art. Resourcefulness and creativity are alive and well in NZ.

Q – Would you ever come home to NZ for good?

I live in the present.